I recently bought tickets to see Robert Caro as part of BAM’s Eat, Drink, and Be Literary series in Brooklyn (if you live in Brooklyn or are visiting, it’s an awesome series). In one of those “what five living people would you have to dinner?” exercises, Caro would be on my list. His bios of Robert Moses (The Power Broker) and LBJ (The Years of Lyndon Johnson – four volumes with a final volume on the way) are absolutely incredible and worth the years it might take you to read them. I’ve read both and they are on my all-time top 10 list. Read them if you can.

In the Q&A section of his talk, I asked Caro a question about LBJ’s “true” self as it relates to his

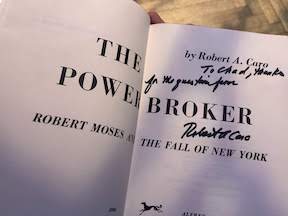

views on race since he may know more about LBJ than any person alive. You can get some sense of it by reading the books but to be able to ask Caro directly was an incredible honor (and an even greater honor to have him sign my copy of The Power Broker and thank me for the question!) He gave such a rich answer that I’m posting it here with no commentary, only a few hyperlinks.

——

Me: Lyndon Johnson was a complex man. On the one hand, some would call him a racist, yet no President had more of an impact on civil rights and voting rights. I’m curious, how do you think about that juxtaposition?

Robert Caro: What you said is one of the most interesting things. For the first 20 years he was in Congress and the Senate, he was 100 percent against civil rights. He voted against every single civil rights bill, even against bills that would have made lynching a crime. He voted against everything.

It wasn’t just his votes. He was a Southern strategist. He was actually the protégé of the Senator Richard Brevard Russell of Georgia, who was the leader of the Southern bloc for 20 years. It was Russell who raised him to power in the Senate. Because Russell believed — Lyndon Johnson made him believe — that he, Lyndon Johnson, hated black people as much as Richard Russell did. It’s then, he said, “This is the same man,” who in 1957 passes the first Civil Rights Act.

Well, the Southerners are still such in power in Congress. Then when he becomes president there for Kennedy’s assassination, there’s this wonderful scene. He has to make a speech to Congress three days after the assassination to a joint session of Congress. He comes down, and he’s still not in the Oval Office of the White House. He’s living in his home in Spring Valley in Washington. His speechwriters — four speechwriters — are downstairs writing his speech. Around midnight, Lyndon Johnson comes down in his bathrobe. and he says, “How are you doing?” They said, “The only thing we’re agreeing on is you must make a priority of civil rights. Try not to mention civil rights, because if you do that, the Southerners are going to do the same thing to you that they did to Kennedy.” “They’re going to stop everything if you try to pass civil rights.” They said, “It’s a noble cause, but it’s a lost cause. Don’t bring it up.” Johnson says, “Well, what the hell’s the presidency for, then?” [I wrote about this on my blog a while back]

In his speech, he says, “The first priority is to pass John Kennedy’s civil rights bill.” [YouTube video – see segment starting at 15:20] To watch him do that, as I said before, I’m not sure we would have it today if he hadn’t been the president then. You say, “Did this man really believe this, or was it politically just expedient?” The reason I feel like no — that he always believed it — is when he was in college, he was very poor. Including his sophomore and junior years, he had to drop out of college and teach elementary school for a year to get enough money to go on. He teaches in this largely Mexican town near the border called Cotulla in Texas. The kids are, after listening and reading the oral histories more than the time he grew up — there are not too many alive. After reading what these children had said later, I wrote, “No teacher had ever cared if these kids learned or not. This teacher cared.”

I feel Lyndon Johnson always wanted to do this. He was writing this great speech, which we all know, the “we shall overcome” speech [YouTube video]. It’s not “them” who must overcome, it’s “we” who must overcome prejudice, and “we” shall overcome. That’s the speechwriter Richard Goodwin, who I asked something like, “How do you know he meant it?” Goodwin said that he wasn’t sure that Johnson did, until Johnson called him and said, “You know, I told you about teaching those kids in Cotulla.” He said, “Well, I’ll tell you something. I swore to myself then that if I ever got power to help them, I would help them. Now, I have the power, and I mean to use it.” I feel like Lyndon Johnson intended to do this all his life when he got power.

You must be logged in to post a comment.